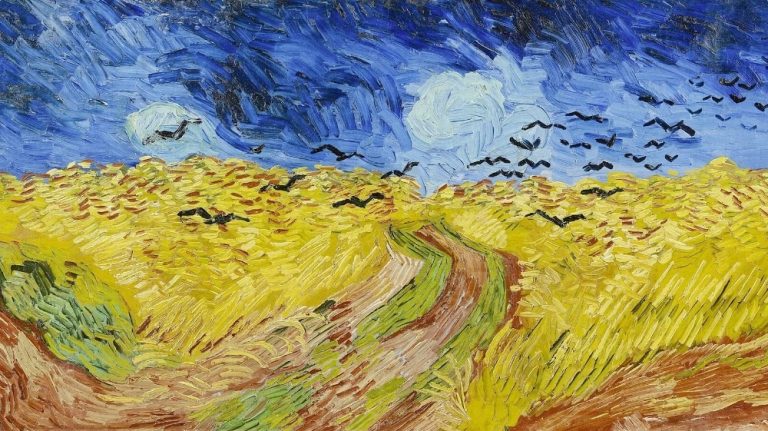

This morning, I went for a walk in the forest with my dog, Ottó. We’ve already lost two balls, so today I brought a ring for him to play with. I was absolutely terrible at it—it’s thrown completely differently than a stick or a ball. In my clumsiness, I either tossed it sideways or dropped it in front of me. I messed up the throws in every possible way. While I was busy overthinking my incompetence, I noticed how joyful Ottó was. He ran back and forth, bringing the ring back and darting off again. He was smiling. He’d been at it for nearly an hour, and even though it was already warm at 5:30 in the morning—even in the forest—and I hadn’t brought any water, his tongue hung out as he wagged his tail, his eyes sparkling with gratitude.

Was he happy?

Even with bad throws, the heat, thirst, and dust? How does he do it? How can he be happy despite all that? Humans have been pondering the question of happiness for ages. Hundreds of literary works explore the topic, philosophers write doctoral theses about it, psychologists delve into its emotional roots, and motivational speakers offer discounted courses promising instant solutions.

But Ottó hasn’t read any of that. And I haven’t taught him a thing about happiness. I taught him to sit, lie down, heel, and stay, but not how to be happy. So how does he know? And why don’t we, despite being so much further along the evolutionary timeline? Could it be that happiness offers no evolutionary advantage? Is it possible that what so many people consider the ultimate purpose of life—the pursuit of happiness—is actually something we lose along the way because it’s a disadvantage in evolutionary terms? If we were happy, would we lose the drive to evolve? Would we stop creating new theories, techniques, and tools to achieve that ever-elusive goal? Happiness?

Ottó is happy.

And, as far as I can tell, he’s evolving too. So what does he know that allows him to succeed where we fail? Granted, he can be quite clueless at times. The ball can be right in front of him, and he won’t see it. He sniffs around, spins in circles, runs back and forth, completely oblivious to the bright red ball lying just ahead. How is his kind supposed to be good at tracking when he can’t even find a neon-colored rubber ball? Does it bother him? When he finally finds it, he bounds toward me with childlike joy, tail wagging. So no, I don’t think he worries much about it.

He just is.

When do I feel that way? When do I stop overthinking and just exist and enjoy? For example, during sex. I’m definitely not analyzing why something feels good in the moment. I’m not mentally running through the biochemical pathways I learned in university, thinking, Ah, so that’s why this is enjoyable—my neurotransmitters are… That would probably ruin the mood. We’re capable of simply experiencing joy without analyzing it.

Does overthinking rob us of happiness? Or is it just hard to be happy and analyze it at the same time? After all, do you think about how to be happy when you already are? I don’t think so. We only think about it when we’re not happy and want to figure out how to be. Understanding it would give us control—tools to pursue it. The desire to understand is embedded in our nature.

So I want to be happy. To achieve that, I need to understand what happiness is, figure out where I am compared to it, and then determine how to get from point A to point B.

But what is happiness?

I’ve read, learned, and heard so much about it. Is it something like the ancient Greeks’ idea of happiness—living a complete, virtuous life? Or is it the ultimate liberation, free from suffering and desire? Or the inner peace and divine joy that stems from spiritual enlightenment? Maybe it’s the American Dream—a mix of wealth, success, and personal freedom? Or, as the Beatitudes say, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.”

Ottó is happy.

And I don’t think he’s worrying about which definition applies. He just is. Maybe it’s because he focuses on doing things he loves and avoids things he doesn’t. And when he does things he dislikes, he doesn’t try to convince himself they’re good or will be worth it in the end. He just tries not to do them. As long as he enjoys chasing the ball, stick, or ring, he doesn’t care if it’s hot or if I only manage to throw it five meters. And if he doesn’t want to keep going, he stops. He’ll lie down at the edge of the path, chewing on a stick, and wait. But if it’s for me, he’ll do it again.

And he’s happy even then.

Is that what we should do? Strip away the overcomplicated methods of pursuing happiness and focus on one thing: what feels good and what doesn’t?

What feels good? Things that energize you, that make your body buzz even when you’re utterly exhausted. And what feels bad? Things that drain the life out of you even when you’re bursting with energy. Isn’t it normal to strive for a life with more and more things that charge you up and fewer that drain you? I get it—there are circumstances we don’t choose, things life or someone else imposes on us. Sometimes it’s tough and unfair.

But the effort to add more of what energizes us and reduce what drains us can, in itself, bring a sense of happiness. It gives us the feeling that each day gets a little better. That we’re moving closer to ourselves.

And that’s progress.

Maybe that’s all happiness really is: those moments when we’re close to being who we truly are.

This article originally appeared on the vendler.hu blog.